Architecture And Reckoning – History In The Making

Madrid's Crystal Palace

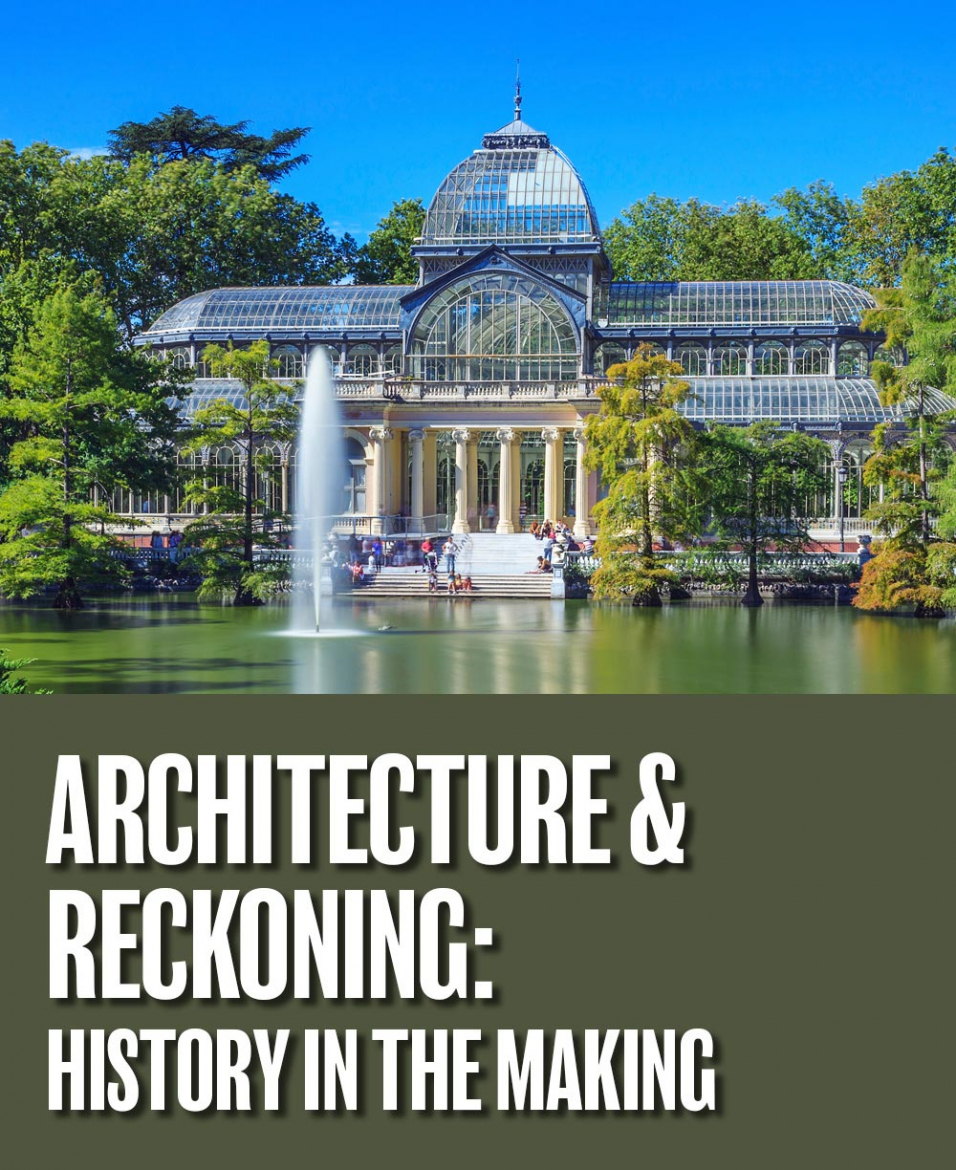

Image: Palacio de Cristal, Madrid, Spain

Scrolling through some of my old photos led to a shocking discovery. The history of the building I was looking at echoes loudly in the present.

The picture I had landed on was a striking view from within the Crystal Palace in El Retiro Park in Madrid, designed by Spanish architect Ricardo Velasquez Bosco. I’ve never been to Spain; the photo was sent to me, but I imagine standing inside would be an experience of expansiveness, its glass walls framing an endless view of the sky. It reminds me of a gothic cathedral whose delicate verticality and light-filled interior create a sense of soaring and awareness of the heavens beyond. Inspired, I decided to research Madrid’s Crystal Palace to discover its original purpose.

The picture I had landed on was a striking view from within the Crystal Palace in El Retiro Park in Madrid, designed by Spanish architect Ricardo Velasquez Bosco. I’ve never been to Spain; the photo was sent to me, but I imagine standing inside would be an experience of expansiveness, its glass walls framing an endless view of the sky. It reminds me of a gothic cathedral whose delicate verticality and light-filled interior create a sense of soaring and awareness of the heavens beyond. Inspired, I decided to research Madrid’s Crystal Palace to discover its original purpose.

Image: Sainte, Chapelle, Paris, France

New Architectural Possibilities in Madrid

As gothic cathedrals stretched the limits of the technology of their time, Madrid’s Crystal Palace was made possible by the Industrial Revolution, which gave rise to industrial structures like railway stations, warehouses, bridges, and factories. Built in 1887 as one of many buildings inspired by Joseph Patton’s Crystal Palace in London, the design was the result of the structural capacities of iron and advanced technology that produced large sheets of glass. Additionally, it was able to be prefabricated, shortening the construction time to an incredible five months. That’s quick, even by today’s standards. But more than an erecter set of parts or an industrial marvel, the design of Velasquez’s Crystal Palace is established by a classical Greek cross plan with elegant massing and fine detailing that includes arched openings, ionic order colonnade, and decorative ceramic tiles created by ceramist Daniel Zuloaga. Beauty, not just function, was in the eye of its creator.

The building showcased modern architectural achievements at the end of the 19th Century. Cast iron was used extensively in railroad stations like Principe Pio Station (North Station), Atocha Station, and the Railway Museum, housed in a renovated train station.

As gothic cathedrals stretched the limits of the technology of their time, Madrid’s Crystal Palace was made possible by the Industrial Revolution, which gave rise to industrial structures like railway stations, warehouses, bridges, and factories. Built in 1887 as one of many buildings inspired by Joseph Patton’s Crystal Palace in London, the design was the result of the structural capacities of iron and advanced technology that produced large sheets of glass. Additionally, it was able to be prefabricated, shortening the construction time to an incredible five months. That’s quick, even by today’s standards. But more than an erecter set of parts or an industrial marvel, the design of Velasquez’s Crystal Palace is established by a classical Greek cross plan with elegant massing and fine detailing that includes arched openings, ionic order colonnade, and decorative ceramic tiles created by ceramist Daniel Zuloaga. Beauty, not just function, was in the eye of its creator.

The building showcased modern architectural achievements at the end of the 19th Century. Cast iron was used extensively in railroad stations like Principe Pio Station (North Station), Atocha Station, and the Railway Museum, housed in a renovated train station.

Image: Leonid Andronov – stock.adobe.com; Atocha Staion, Madrid, Spain

Image: “ESTACION PRINCIPE PIO MADRID 6794 18-1-2017” by Jose Javier Martin Espartosa is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Other examples of cast iron architecture in Madrid include San Miguel Market and another Ricardo Velazquez Bosco design, namesake Velazquez Palace, built four years earlier than its neighboring Crystal

A Darker Past

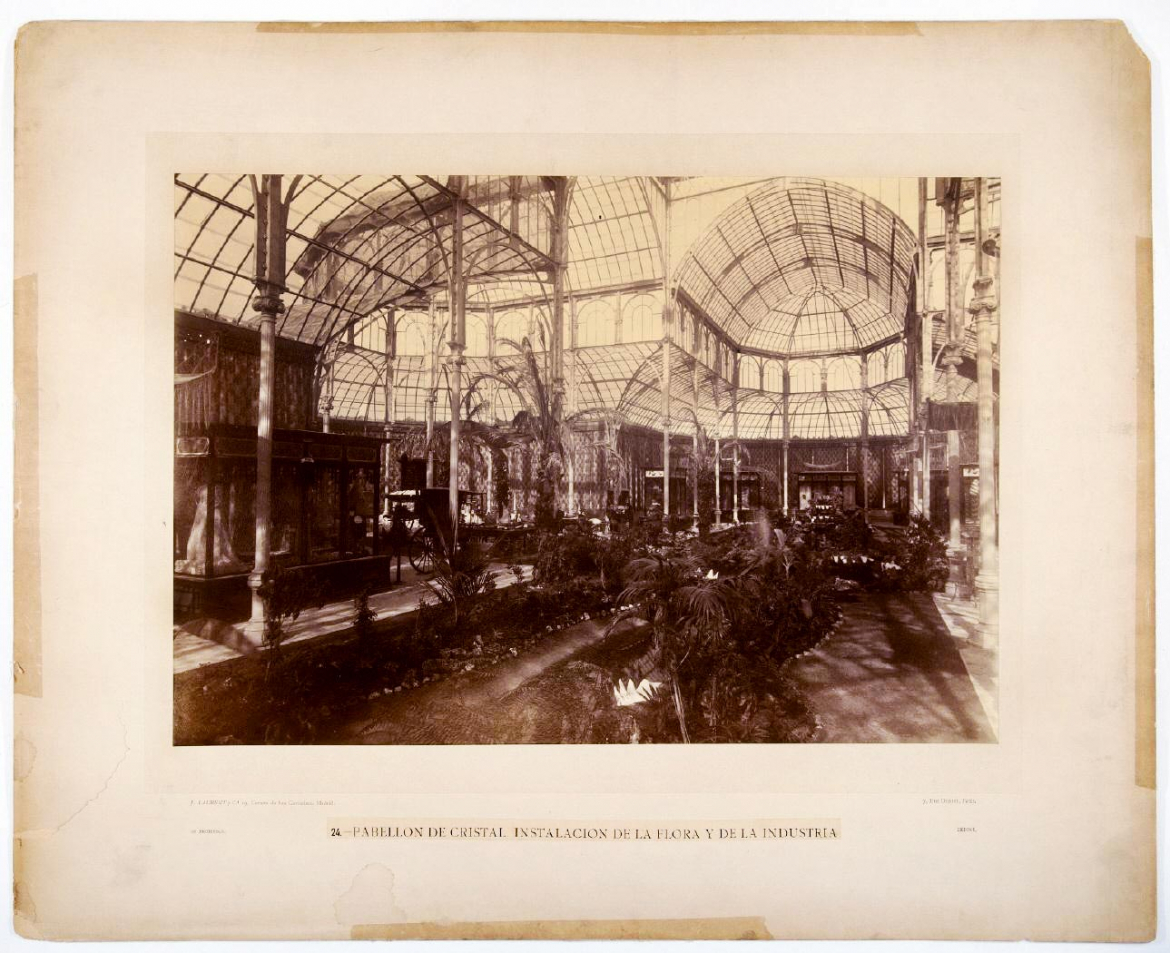

Image: J. Laurent y Cía, National Museum of Anthropology. Catalog of Collections of the National Museum of Anthropology (http://mnantropologia.mcu.es), Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports, Spain

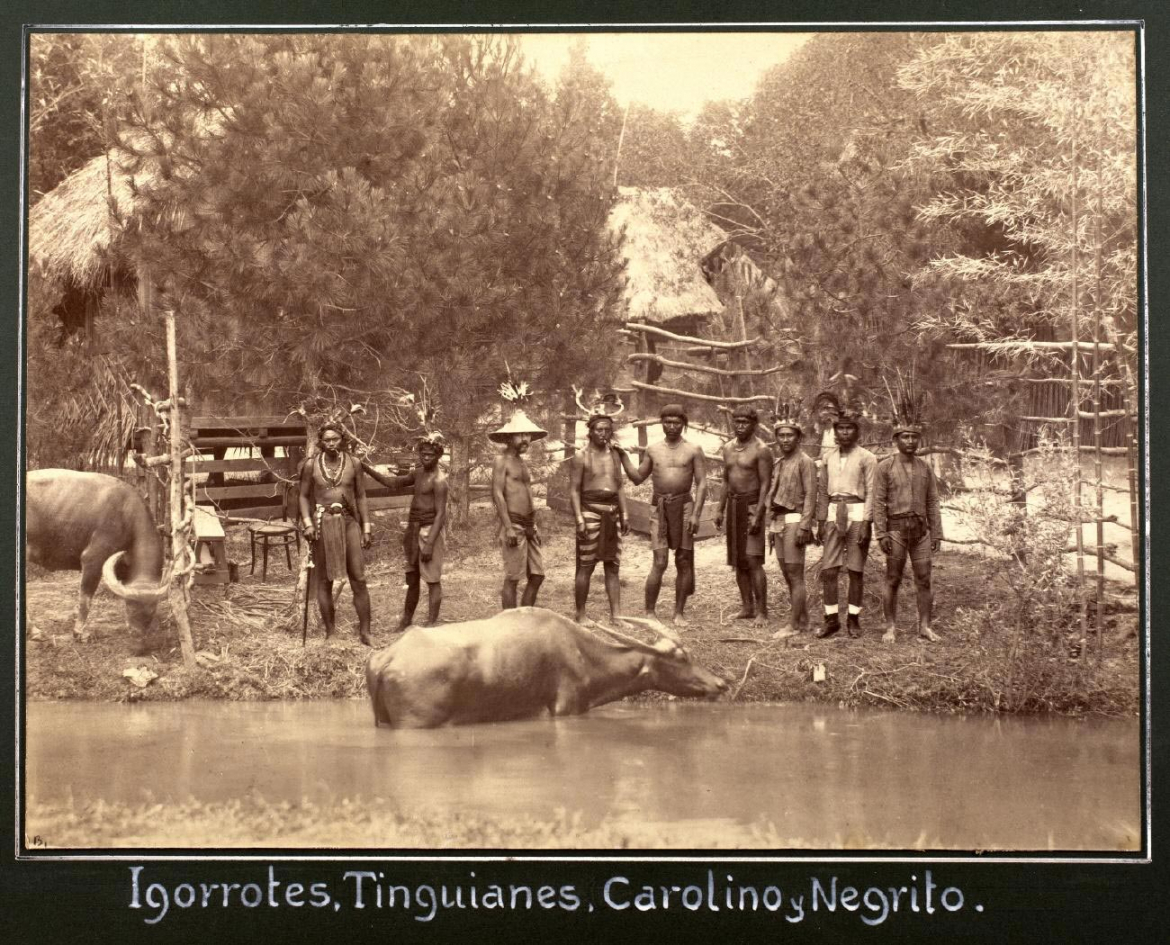

So, while the Crystal Palace was a modern gem showcasing technological advancements in a stunning light-filled structure, there was also a darker side to its beginning. It was conceived to exhibit life as found in the far-away Philippines, a Spanish colony at the time. Hosting the first Exposicion General De Las Islas Filipinas (Exhibition of the Philippines) in 1887, the glass conservatory exhibited flora, fauna, and artifacts brought back from the islands. It could be called a living history exhibit, but some called it a human zoo – in addition to flora and fauna, humans were on display. Spanish colonizers brought forty-three men and women of the Igorot Tribe from the mountains of the Philippine Island of Luzon to enact pre-colonial daily life while spectators watched. A small village was built next to the Palace that included a pond for their hollowed-out canoes and small farms to plow using cattle. According to Leah Pattem, writing for gal-dem, the Filipinos were “required to wear folk costumes, carry spears and perform daily ceremonies involving the sacrificial slaughter of animals.” While part of the organizers’ intent may have been to showcase Spain’s beneficial influence on the indigenous people in the waning colonial period, the exhibit painted them in a barbaric light, heightening racist attitudes.

Image: J. Laurent y Cía, National Museum of Anthropology. Catalog of Collections of the National Museum of Anthropology (http://mnantropologia.mcu.es), Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports, Spain

Woefully, Spain is not unique in this type of dehumanizing exhibit. Colonized peoples were exhibited in “ethnic shows” and “human zoos” throughout Western Europe and the US into the 20th Century. In fact, the United States government transported one thousand Igorot people to the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis.

Full Circle at the Crystal Palace

Today, the Museo Nacional de Arte Sofia owns the Glass Palace and the Velazquez Palace and uses them for seasonal art exhibits. Recently, on the 500th anniversary of Magellan claiming the Philippines for Spain, the Glass Palace hosted a show by Filipino artist Kidlat Tahimik, who retold the story of the Philippines’ conquest by Spain through the eyes of the colonized. The epic breadth of the show included an installation devoted to the original Glass Palace exhibition and its contemporary critic Jose’ Rizal, an author and advocate born in the Philippines and who attended the University of Madrid for post-graduate work. Rizal was executed in Manila in 1896 at the age of thirty-six by Spanish authorities for his call for reforms in the colony. His death sparked the revolt against Spanish rule, resulting in the nation’s independence in 1898.

Full Circle at the Crystal Palace

Today, the Museo Nacional de Arte Sofia owns the Glass Palace and the Velazquez Palace and uses them for seasonal art exhibits. Recently, on the 500th anniversary of Magellan claiming the Philippines for Spain, the Glass Palace hosted a show by Filipino artist Kidlat Tahimik, who retold the story of the Philippines’ conquest by Spain through the eyes of the colonized. The epic breadth of the show included an installation devoted to the original Glass Palace exhibition and its contemporary critic Jose’ Rizal, an author and advocate born in the Philippines and who attended the University of Madrid for post-graduate work. Rizal was executed in Manila in 1896 at the age of thirty-six by Spanish authorities for his call for reforms in the colony. His death sparked the revolt against Spanish rule, resulting in the nation’s independence in 1898.

Image: Palacio de Cristal, Madrid, Spain

The Glass Palace remains a beautiful architectural gem, though its original purpose casts a shadow on its legacy. Activists criticized its 2021 inclusion with El Retiro Park as part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site based on its history. That’s part of the reckoning that comes with history and conquest.

Diversity and Inclusion in Architecture Today

It’s refreshing for past injustice to be acknowledged and even illuminated in the same Crystal Palace considered a jewel of the Industrial Revolution, an enlightened age. In our age of further enlightenment, where appreciation of diversity and inclusion far exceeds 19th Century norms, how does architecture relate to how we view each other, culturally and racially?

Great museums bear witness to historical racial and ethnic struggles, like the African American Museum (Freelon Adjaye Bond/SmithGroup), the Holocaust Museum (James Ingo Freed of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners), and the Museum of the American Indian (Douglas Cardinal; Jones, House, and Sakiestew; Jones & Jones; SmithGroup; Lou Weller; Native American Design Collaborative; Polshek Partnership Architects), all located along the National Mall in Washington, DC. In New Orleans, Manning has been fortunate to help bring another example of living history to life in the Tate Etienne Provost Interpretive Center (TEP Center). The purpose of the renovation of the McDonough 19 school is to capture its history as the site of school integration in New Orleans. The school, once vacated by Whites upon integration by three Black first-graders in 1960, now presents the story of integration through the eyes of Leona Tate, Gail Etienne, and Tessie Prevost with interactive exhibits and an oral history component where visitors can contribute their own stories. Not unlike Tahimik’s retelling of the colonization story from the perspective of Filipinos, visitors to the TEP Center will virtually walk in the steps of three six-year-olds escorted by federal marshals to school.

And as the TEP Center story rests on the shoulders of Tate, Etienne, and Prevost, we are inspired by another titan advancing diversity and inclusion: Carolyn Barber-Pierre, who, for over thirty-five years, has helped underrepresented students at Tulane University feel safe and welcome, contributing to their academic success at the university. Manning principal Dominic Willard, one of the students who attribute Barber-Pierre with making a positive difference in his academic career as an African American in Tulane’s School of Architecture, affirms, “I fondly recall my days spent hanging out in the basement of the University Center before it was transformed into the amazing space that it has become. Although it was a small, windowless space, it was always one where students of varying races, ethnicities, and religions could gather and feel comfortable and safe. Credit for that goes to Carolyn and the culture of acceptance she created. She provided safe space and helped me to feel accepted, and that let me focus on the rigors of school.” In a full-circle moment, Dominic led the renovation of the historic Richardson Hall into the Carolyn Barber-Pierre Center for Intercultural Life and Academic Equity, providing a hub on campus for students of all backgrounds and identities to find acceptance and flourish.

Diversity and Inclusion in Architecture Today

It’s refreshing for past injustice to be acknowledged and even illuminated in the same Crystal Palace considered a jewel of the Industrial Revolution, an enlightened age. In our age of further enlightenment, where appreciation of diversity and inclusion far exceeds 19th Century norms, how does architecture relate to how we view each other, culturally and racially?

Great museums bear witness to historical racial and ethnic struggles, like the African American Museum (Freelon Adjaye Bond/SmithGroup), the Holocaust Museum (James Ingo Freed of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners), and the Museum of the American Indian (Douglas Cardinal; Jones, House, and Sakiestew; Jones & Jones; SmithGroup; Lou Weller; Native American Design Collaborative; Polshek Partnership Architects), all located along the National Mall in Washington, DC. In New Orleans, Manning has been fortunate to help bring another example of living history to life in the Tate Etienne Provost Interpretive Center (TEP Center). The purpose of the renovation of the McDonough 19 school is to capture its history as the site of school integration in New Orleans. The school, once vacated by Whites upon integration by three Black first-graders in 1960, now presents the story of integration through the eyes of Leona Tate, Gail Etienne, and Tessie Prevost with interactive exhibits and an oral history component where visitors can contribute their own stories. Not unlike Tahimik’s retelling of the colonization story from the perspective of Filipinos, visitors to the TEP Center will virtually walk in the steps of three six-year-olds escorted by federal marshals to school.

And as the TEP Center story rests on the shoulders of Tate, Etienne, and Prevost, we are inspired by another titan advancing diversity and inclusion: Carolyn Barber-Pierre, who, for over thirty-five years, has helped underrepresented students at Tulane University feel safe and welcome, contributing to their academic success at the university. Manning principal Dominic Willard, one of the students who attribute Barber-Pierre with making a positive difference in his academic career as an African American in Tulane’s School of Architecture, affirms, “I fondly recall my days spent hanging out in the basement of the University Center before it was transformed into the amazing space that it has become. Although it was a small, windowless space, it was always one where students of varying races, ethnicities, and religions could gather and feel comfortable and safe. Credit for that goes to Carolyn and the culture of acceptance she created. She provided safe space and helped me to feel accepted, and that let me focus on the rigors of school.” In a full-circle moment, Dominic led the renovation of the historic Richardson Hall into the Carolyn Barber-Pierre Center for Intercultural Life and Academic Equity, providing a hub on campus for students of all backgrounds and identities to find acceptance and flourish.

Image: Carolyn Barber-Pierre, ©2021 Tulane University | Paula Burch-Celetano

The Crystal Palace is a good lesson. We are honored to be a part of interpreting the lessons we’ve learned using design as a vehicle. Learning from history, looking through the eyes of others, and gratitude for the trailblazers before us contribute to our participation in the evolving story of equity and inclusion.