Imagining Community Wellness - Reframing Healthcare Options In New Orleans

Just before Hurricane Katrina hit, I slipped three back-up tapes for the company’s server in my pocket and evacuated. That small act made it possible for our office to operate remotely post-Katrina. That’s part of my resiliency story.

Resiliency is made up of the thousands of individual stories that combine into a community’s shared experience. In New Orleans, those stories are everywhere. We can look around us and see how things have changed since Hurricane Katrina’s floods caused the mass evacuation of our city. Some folks didn’t make it back, but most did. Katrina didn’t win; we are resilient.

The 64,000+ residents of New Orleans East are predominantly African American with a median household income of $30,958, thirty-eight percent below the state at large. They are separated from downtown and the rest of the city by the Industrial Canal and it’s crossing, the interstate “high-rise” bridge. The height and distance of that crossing was a barrier for residents who sought healthcare. In fact, even in an ambulance, the time it took to reach an emergency room proved fatal for some. The construction of the hospital was a huge boon to the East in provision of healthcare and also as a catalyst for recovery. With a hospital available, investment in other developments made sense. That’s another resiliency story. But there’s more work to be done as part of our continuing resiliency story, particularly in the healthcare arena.

Healthcare Resiliency in New Orleans

Since that storm, in New Orleans we’ve improved our physical infrastructure, renovated and built new schools and libraries, and opened a new airport. And finally, we rebuilt a hospital in suburban New Orleans East, a community that went without a hospital in the nine years post Hurricane Katrina. Manning was honored to be a part of the architectural team for the New Orleans East Hospital.The 64,000+ residents of New Orleans East are predominantly African American with a median household income of $30,958, thirty-eight percent below the state at large. They are separated from downtown and the rest of the city by the Industrial Canal and it’s crossing, the interstate “high-rise” bridge. The height and distance of that crossing was a barrier for residents who sought healthcare. In fact, even in an ambulance, the time it took to reach an emergency room proved fatal for some. The construction of the hospital was a huge boon to the East in provision of healthcare and also as a catalyst for recovery. With a hospital available, investment in other developments made sense. That’s another resiliency story. But there’s more work to be done as part of our continuing resiliency story, particularly in the healthcare arena.

Health Equity

I am grieving the recent loss of my mother because of a new disaster—the coronavirus pandemic. Bessie Lee would have turned 90 on her birthday. She was a fierce fighter. She was also elderly, African American, and suffered from Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). She hardly had a swinging chance against COVID-19. And her story is repeated over and over again by the thousands.

Though longstanding, the coronavirus pandemic has spotlighted the health disparity in the African American community. In May, MedPage Today reported that African Americans account for 70% of COVID-19 deaths in Louisiana while they only represent a third of the total population. Why? The article goes on to say that “African Americans shoulder a higher burden of chronic disease, with 40% higher rates of hypertension and 60% higher rate of diabetes than white Americans, both of which have been tied to negative COVID-19 outcomes” (Hlavinka 2020). The underlying conditions that plague the African American community contribute to the troubling statistics.

But there’s good news in this gloomy picture. We can combat and reverse many of these conditions.

Though longstanding, the coronavirus pandemic has spotlighted the health disparity in the African American community. In May, MedPage Today reported that African Americans account for 70% of COVID-19 deaths in Louisiana while they only represent a third of the total population. Why? The article goes on to say that “African Americans shoulder a higher burden of chronic disease, with 40% higher rates of hypertension and 60% higher rate of diabetes than white Americans, both of which have been tied to negative COVID-19 outcomes” (Hlavinka 2020). The underlying conditions that plague the African American community contribute to the troubling statistics.

But there’s good news in this gloomy picture. We can combat and reverse many of these conditions.

Community Wellness

Attacking the health disparity means elevating wellness. The solution goes beyond delivering healthcare to changing behavior. Exercise and eating right are the front lines of the battle. There’s no shortage of data on this, so why aren’t we all practicing healthy habits, wiping out obesity, diabetes, and clogged arteries in great swaths?

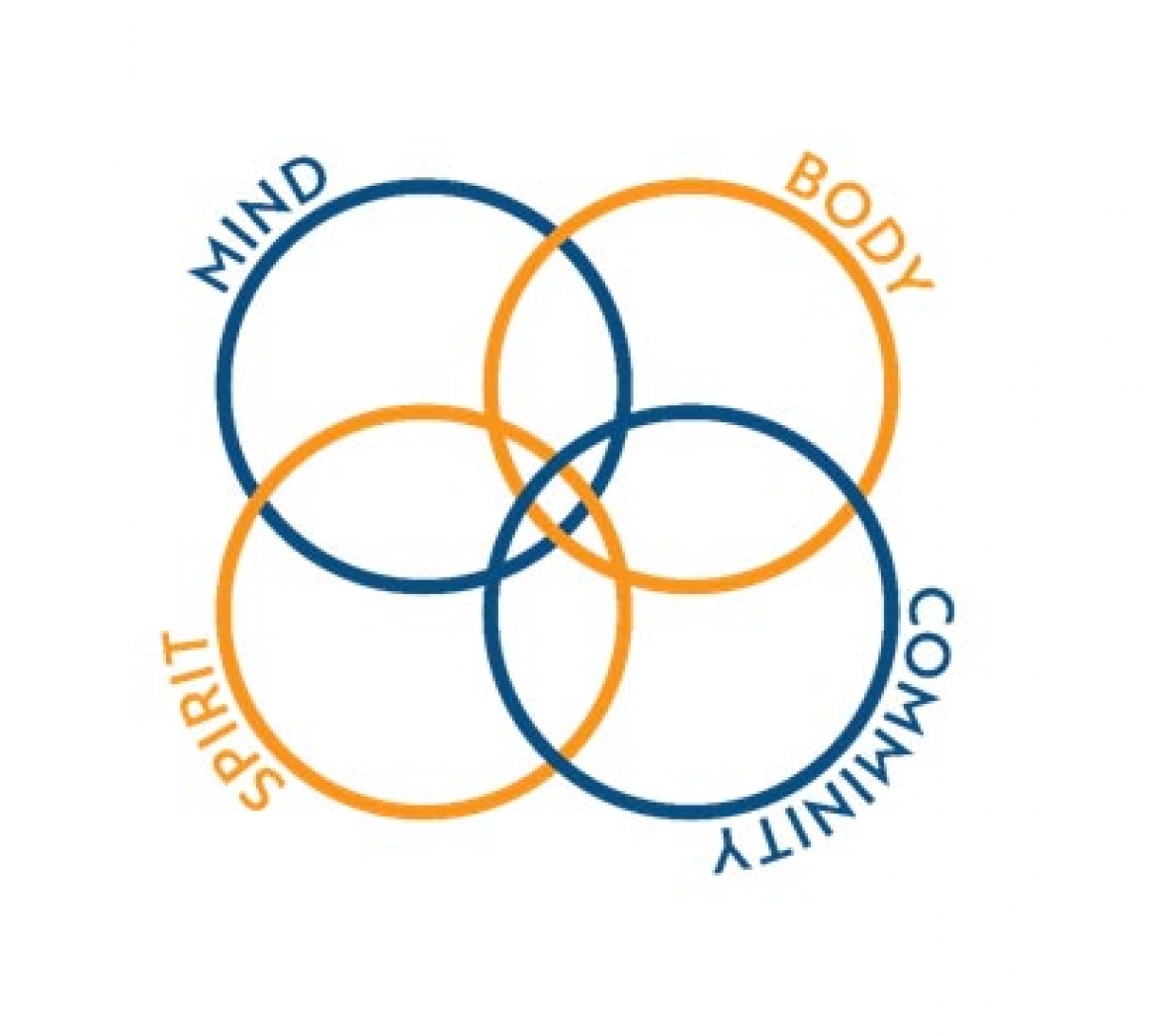

Wellness is more than just our weight and blood test results, and we need more than information to affect lifestyle changes. Wellness encompasses the entire human experience. We are well when we are physically healthy, also when we account for our emotions and we feel healthy—we feel welcome, hopeful, and like we matter. It starts there—at the point of making real and positive connections with people, in their communities. That has the power to transform lifestyles.

Creating a place that forges connection with its community members, that invites them in and cares for the needs of the whole person beyond what we normally think of as healthcare, can supply the access to wellness that will make the difference. We must address the sick, the well, the old, the young, individuals, and families. Those who work long hours, students, and those with impairments. Wellness is for everyone.

While we want wellness for everyone, let’s start with one person. Let’s call him Henry. Henry, a lineman for the power company, injures his leg in an accident, and it requires surgery. The surgery goes well! He spends a few days in the hospital recovering before being discharged. But so soon after surgery, he can’t walk very well. His doctors prescribe physical therapy at the place a few miles down the highway. Henry dutifully goes to physical therapy, wondering when he’ll be able to go back to work. His wife, Gloria, drives him, so they have to go when she’s not working. It’s a struggle to make schedules mesh, so appointments get spaced out and progress is slow. But eventually, Henry is cleared to go back to work. He feels much stronger, even if not quite a hundred percent, even if he’s put on fifteen pounds since he hasn’t been active for months. But Henry’s a fighter. He decides to walk in the evenings after work to drop the weight and strengthen his leg. But his neighborhood doesn’t have sidewalks, so he has to drive to the park, leaving his wife without the car. Gloria isn’t happy. Since she doesn’t have a car to go grocery shopping, she tells Henry to pick up fried chicken from Popeye’s on his way home—four nights this week. Henry’s leg is better, but he’s not losing the weight he’d hoped, and now Gloria’s clothes are fitting tighter too.

What if Henry were actually Henrietta? She doesn’t feel comfortable walking after nightfall and can’t afford a gym membership. She keeps gaining weight. It’s depressing. Or maybe she’s a single mom and doesn’t have childcare and never makes it to the first physical therapy appointment because who’d watch the kids? She can’t go back to work. She’s depressed and anxious about the future. Her doctor prescribes insulin and Xanax.

Or, what if there was a place where Henry and Henrietta could go, where they felt comfortable, where they could get an assessment of their needs and a plan of action, PT and OT steps away from the hospital where they had surgery, where they could walk or jog and take cooking classes using healthy produce so they develop the habits that keep them from ever needing insulin? What if Henrietta’s kids went with her and took swimming lessons or ACT prep classes or played with peers under supervised care while she was in therapy?

The point is, a campus that functions as a community center for wellness could change lives. New Orleans East is a great model community, where it’s possible to build upon the asset of the hospital and expand it into a campus of wellness and health that provides rehabilitation, fitness, education, and a host of services to address the full scope of needs that keep people from experiencing wellness.

I am suggesting access to wellness is as important as access to healthcare. As crucial as opening the hospital in New Orleans East was for that community, taking it a step further is also vital.

Wellness is more than just our weight and blood test results, and we need more than information to affect lifestyle changes. Wellness encompasses the entire human experience. We are well when we are physically healthy, also when we account for our emotions and we feel healthy—we feel welcome, hopeful, and like we matter. It starts there—at the point of making real and positive connections with people, in their communities. That has the power to transform lifestyles.

Creating a place that forges connection with its community members, that invites them in and cares for the needs of the whole person beyond what we normally think of as healthcare, can supply the access to wellness that will make the difference. We must address the sick, the well, the old, the young, individuals, and families. Those who work long hours, students, and those with impairments. Wellness is for everyone.

While we want wellness for everyone, let’s start with one person. Let’s call him Henry. Henry, a lineman for the power company, injures his leg in an accident, and it requires surgery. The surgery goes well! He spends a few days in the hospital recovering before being discharged. But so soon after surgery, he can’t walk very well. His doctors prescribe physical therapy at the place a few miles down the highway. Henry dutifully goes to physical therapy, wondering when he’ll be able to go back to work. His wife, Gloria, drives him, so they have to go when she’s not working. It’s a struggle to make schedules mesh, so appointments get spaced out and progress is slow. But eventually, Henry is cleared to go back to work. He feels much stronger, even if not quite a hundred percent, even if he’s put on fifteen pounds since he hasn’t been active for months. But Henry’s a fighter. He decides to walk in the evenings after work to drop the weight and strengthen his leg. But his neighborhood doesn’t have sidewalks, so he has to drive to the park, leaving his wife without the car. Gloria isn’t happy. Since she doesn’t have a car to go grocery shopping, she tells Henry to pick up fried chicken from Popeye’s on his way home—four nights this week. Henry’s leg is better, but he’s not losing the weight he’d hoped, and now Gloria’s clothes are fitting tighter too.

What if Henry were actually Henrietta? She doesn’t feel comfortable walking after nightfall and can’t afford a gym membership. She keeps gaining weight. It’s depressing. Or maybe she’s a single mom and doesn’t have childcare and never makes it to the first physical therapy appointment because who’d watch the kids? She can’t go back to work. She’s depressed and anxious about the future. Her doctor prescribes insulin and Xanax.

Or, what if there was a place where Henry and Henrietta could go, where they felt comfortable, where they could get an assessment of their needs and a plan of action, PT and OT steps away from the hospital where they had surgery, where they could walk or jog and take cooking classes using healthy produce so they develop the habits that keep them from ever needing insulin? What if Henrietta’s kids went with her and took swimming lessons or ACT prep classes or played with peers under supervised care while she was in therapy?

The point is, a campus that functions as a community center for wellness could change lives. New Orleans East is a great model community, where it’s possible to build upon the asset of the hospital and expand it into a campus of wellness and health that provides rehabilitation, fitness, education, and a host of services to address the full scope of needs that keep people from experiencing wellness.

I am suggesting access to wellness is as important as access to healthcare. As crucial as opening the hospital in New Orleans East was for that community, taking it a step further is also vital.

Success Doesn’t Happen by Chance

Access to wellness, to be successful, must be created and managed with intention. The process should start with a survey of the community: what it lacks, what are the barriers to wellbeing to overcome, what might improve health.

Concurrently, an online summit that brings together leaders in the healthcare world, other pertinent experts, and community stakeholders, could spearhead innovations and best practices to combat the blight of the healthcare disparity, steering a path forward for this community. A survey of similar efforts occurring over the globe can be useful, but having experts addressing the specific problems of the specific community is ideal.

An ongoing dialogue with community members to set goals and frame the vision is crucial in understanding the needs of the community as well as engaging people in the process. The development team needs to hear the stories of the Henrys and Henriettas to understand the challenges they face. The community should “own” the project so that they feel comfortable and know they will be cared for and treated with dignity.

Existing resources can also be tapped, such as the master plan developed for the Parish Hospital Service District for the 22-acre New Orleans East Hospital site. The master plan integrated a range of uses on the site and identified additional assets adjacent to it, creating a walkable, livable community that considers the full range of the human experience. Visitors to the site, or those that live on campus or nearby, have access to healthcare, housing, retail, worship, education, and recreation. This holistic thinking applies directly to wellness, given the premise that wellness is a function of the entire person.

In this holistic vein, a spectrum of program offerings that would engage residents and support wellness should be explored. These might include:

In this one-stop-shop wellness setting, research and medical instruction, such as a nursing school, could even be integrated with the hospital and wellness activities to create a complete environment of healthcare innovation and practice, serving the immediate community and beyond. Partnerships with outside entities—research hospitals like the Mayo Clinic or associations such as the American Diabetes Association—could also be explored to strengthen the impact of this health and wellness center.

Working together—client, advisors, design team, construction team, and community members—the development team can develop a program that offers value to the community and to investors. Once a facility program is developed and a vision conceptualized, organizers can use the data and graphic materials to raise needed funds.

This integrated team relationship will be critical as the project progresses through the design and construction phases to keep the project on track, meeting its budget and schedule goals.

Concurrently, an online summit that brings together leaders in the healthcare world, other pertinent experts, and community stakeholders, could spearhead innovations and best practices to combat the blight of the healthcare disparity, steering a path forward for this community. A survey of similar efforts occurring over the globe can be useful, but having experts addressing the specific problems of the specific community is ideal.

An ongoing dialogue with community members to set goals and frame the vision is crucial in understanding the needs of the community as well as engaging people in the process. The development team needs to hear the stories of the Henrys and Henriettas to understand the challenges they face. The community should “own” the project so that they feel comfortable and know they will be cared for and treated with dignity.

Existing resources can also be tapped, such as the master plan developed for the Parish Hospital Service District for the 22-acre New Orleans East Hospital site. The master plan integrated a range of uses on the site and identified additional assets adjacent to it, creating a walkable, livable community that considers the full range of the human experience. Visitors to the site, or those that live on campus or nearby, have access to healthcare, housing, retail, worship, education, and recreation. This holistic thinking applies directly to wellness, given the premise that wellness is a function of the entire person.

In this holistic vein, a spectrum of program offerings that would engage residents and support wellness should be explored. These might include:

- Pocket park, integrating nature

- Outdoor walking track

- Indoor track

- Education (cooking classes, health classes, dance classes, get to college, etc.)

- Featured health programs (health fairs and events sponsored by medical associations, institutes, etc.)

- Teaching kitchen

- Community garden

- Fresh produce market

- Fitness center

- Weight management center

- Aquatics center

- Physical and occupational therapy

- Other therapies

- Imaging

- Arts programs

- Childcare

- Computer labs

- Community programs

- Hair salon

- Café

- Outdoor recreation fields/courts

- Indoor sports courts

In this one-stop-shop wellness setting, research and medical instruction, such as a nursing school, could even be integrated with the hospital and wellness activities to create a complete environment of healthcare innovation and practice, serving the immediate community and beyond. Partnerships with outside entities—research hospitals like the Mayo Clinic or associations such as the American Diabetes Association—could also be explored to strengthen the impact of this health and wellness center.

Working together—client, advisors, design team, construction team, and community members—the development team can develop a program that offers value to the community and to investors. Once a facility program is developed and a vision conceptualized, organizers can use the data and graphic materials to raise needed funds.

This integrated team relationship will be critical as the project progresses through the design and construction phases to keep the project on track, meeting its budget and schedule goals.

Vision for Wellness

While it’s too early to say what such a wellness center would look like, I imagine a welcoming place that people will be eager to visit, that will feel comfortable and give them confidence. They’ll come to learn, socialize, have fun, and stay healthy. I imagine a place that integrates nature into the design, incorporates natural light, and uses sustainable materials without harmful chemicals. A design that is flexible to change with the needs of the community, and one that provides value. A vibrant design permeated with humanity.

I imagine a community elevated by better health outcomes—a well community. Let this be our next resiliency story.

References

Elizabeth Hlavinka, “COVID-19 Killing African Americans at Shocking Rates,” MedPage Today, May 1, 2020, https://www.medpagetoday.com/infectiousdisease/covid19/86266.

I imagine a community elevated by better health outcomes—a well community. Let this be our next resiliency story.

References

Elizabeth Hlavinka, “COVID-19 Killing African Americans at Shocking Rates,” MedPage Today, May 1, 2020, https://www.medpagetoday.com/infectiousdisease/covid19/86266.