RAIL Renaissance – Making the Case for a Renewed Baton Rouge to New Orleans Intercity Passenger Rail

Rebirth of Rail Transit in the United States

In 2018, the first privately funded passenger rail in over a century went into operation. The Florida Brightline, now re-branded as Virgin Trains USA, connects commuters from Downtown Miami to West Palm Beach and will ultimately pass through the Orlando theme parks, reaching Tampa. In Texas, construction of a Japanese-inspired high-speed bullet train connecting Dallas and Houston, which will be able to travel at speeds of up to 200 miles per hour, is expected to commence in 2019 with private funding.Public/Private Partnerships

The private sector has begun to recognize the business opportunities of a revitalized and enhanced passenger rail network throughout the United States. Americans are no longer content to sit in their vehicles through ever-increasing commuting times – time that can be better spent with friends and family, conducting business, or pursuing other interests. On the public sector side, municipalities are finally beginning to recognize that massive investments in highway widening only exacerbate traffic congestion in the long-term and that a more wholistic, efficient, and sustainable approach to mobility planning is needed. The story of passenger rail in the New Orleans and Baton Rouge metropolitan areas, and the communities in between, is a story that repeats itself in cities across the country.History of Passenger Rail in Southeast Louisiana

Passenger rail in New Orleans dates back to 1831 when the Pontchartrain Railroad was established, connecting Lake Pontchartrain and the French Quarter. Over the next century, New Orleans established itself as a hub of passenger rail in the Gulf South, with over a half-dozen passenger rail stations throughout the City. Rail operation of these stations was consolidated in the 1950’s with the construction of the Union Passenger Terminal, which would serve as New Orleans’ sole rail gateway. However, passenger rail began to decline over the ensuing decades. Rubber tire buses were hailed as the next technological advancement in passenger mobility and began to slowly take over train and streetcar operations.By the 1970’s, Interstate-10 connecting New Orleans and Baton Rouge was completed, giving the private automobile a new high-speed corridor between the two metros. During this time, the quasi-public National Railroad Passenger Corporation, more widely known as Amtrak, was created and took over the passenger rail services previously being provided by private freight rail operators at a financial loss. In 1974, Amtrak terminated the Baton Rouge to New Orleans passenger rail service.

Modern Rail Transit – New Orleans to Baton Rouge

Since termination of the Baton Rouge to New Orleans intercity rail, vehicular traffic along the I-10 has steadily increased between the two metros. An estimated 50,000 commuters now travel between New Orleans and Baton Rouge for work and have no choice but to sit in bumper-to-bumper traffic daily. In May 2019, a new world-class airport terminal will open at New Orleans’ Louis Armstrong International Airport and is projected to generate additional traffic with the increased number of flights being offered to a wider range of destinations. Without a high capacity transit system connecting New Orleans and Baton Rouge to the airport, traffic and commuting times will only continue to worsen.The Opportunity

We are reaching a tipping point socially, environmentally, and economically. Transportation accounts for nearly one-third of all greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. The average American is paying more for transportation than for food, while commuting times continue to rise. A widespread passenger rail network can start alleviating these pressures on our limited resources. Rail has a lower carbon footprint than both driving and flying, and its widespread use can drastically cut greenhouse gas emissions. With a robust transit network, those who cannot afford a vehicle no longer need to rely on one to move around. A well-planned rail system also has the ability to catalyze transit-oriented developments that enable car-free lifestyles.

The Florida Brightline, now Virgin Trains USA, is the first privately-funded passenger rail in the United States in over a century. BBT609 [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)]

Fruitvale Transit Village in Oakland, CA: a successful transit-oriented development adjacent to a Bay Area Rapid Transit stop, with a mix of commercial, residential, and community uses.

Flip619 at English Wikipedia [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)]

Flip619 at English Wikipedia [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)]

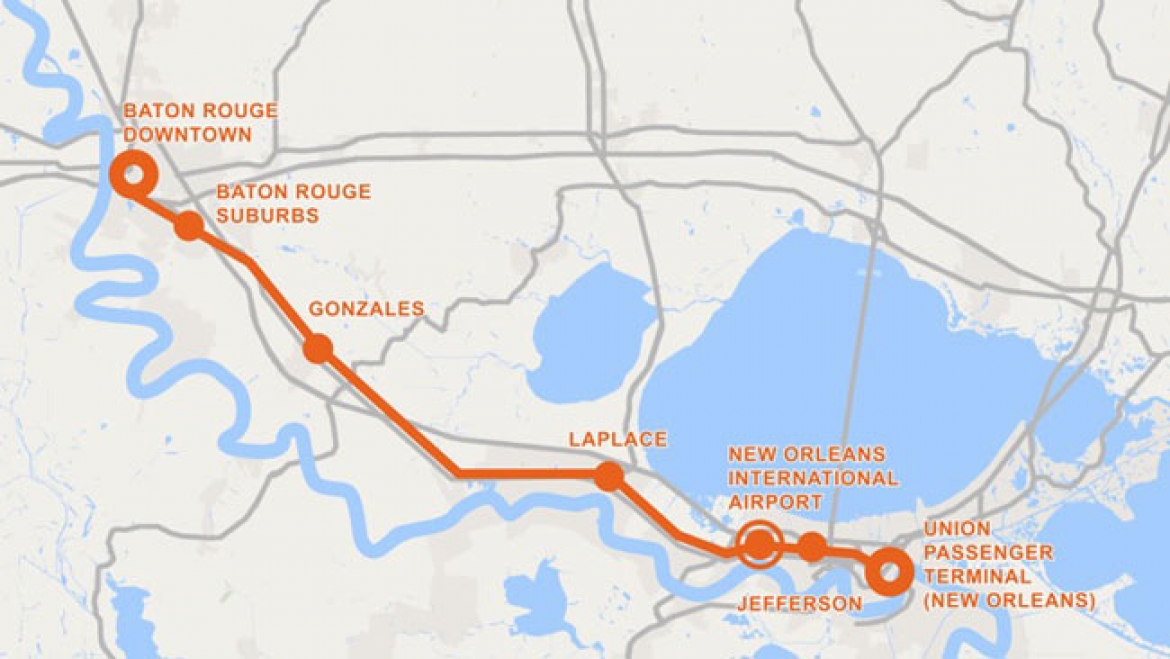

Discussions around a renewed passenger rail system connecting New Orleans and Baton Rouge have carried on almost since service was terminated in 1974 and have gained momentum especially in recent years. After Hurricane Katrina, it became apparent that New Orleans needed a comprehensive evacuation strategy and that passenger rail would be a logical component. A feasibility study completed in 2014 for an intercity rail system included potential route alignments, station area locations, and funding mechanisms. Rail station master plans have been completed for Baton Rouge, Gonzales, LaPlace, and New Orleans. A poll conducted in 2019 of Louisiana residents living between Baton Rouge and New Orleans shows overwhelming support of an intercity rail system. 85% of respondents indicated that passenger rail service between Baton Rouge and New Orleans is important and 63% indicated that they would be likely to utilize it.

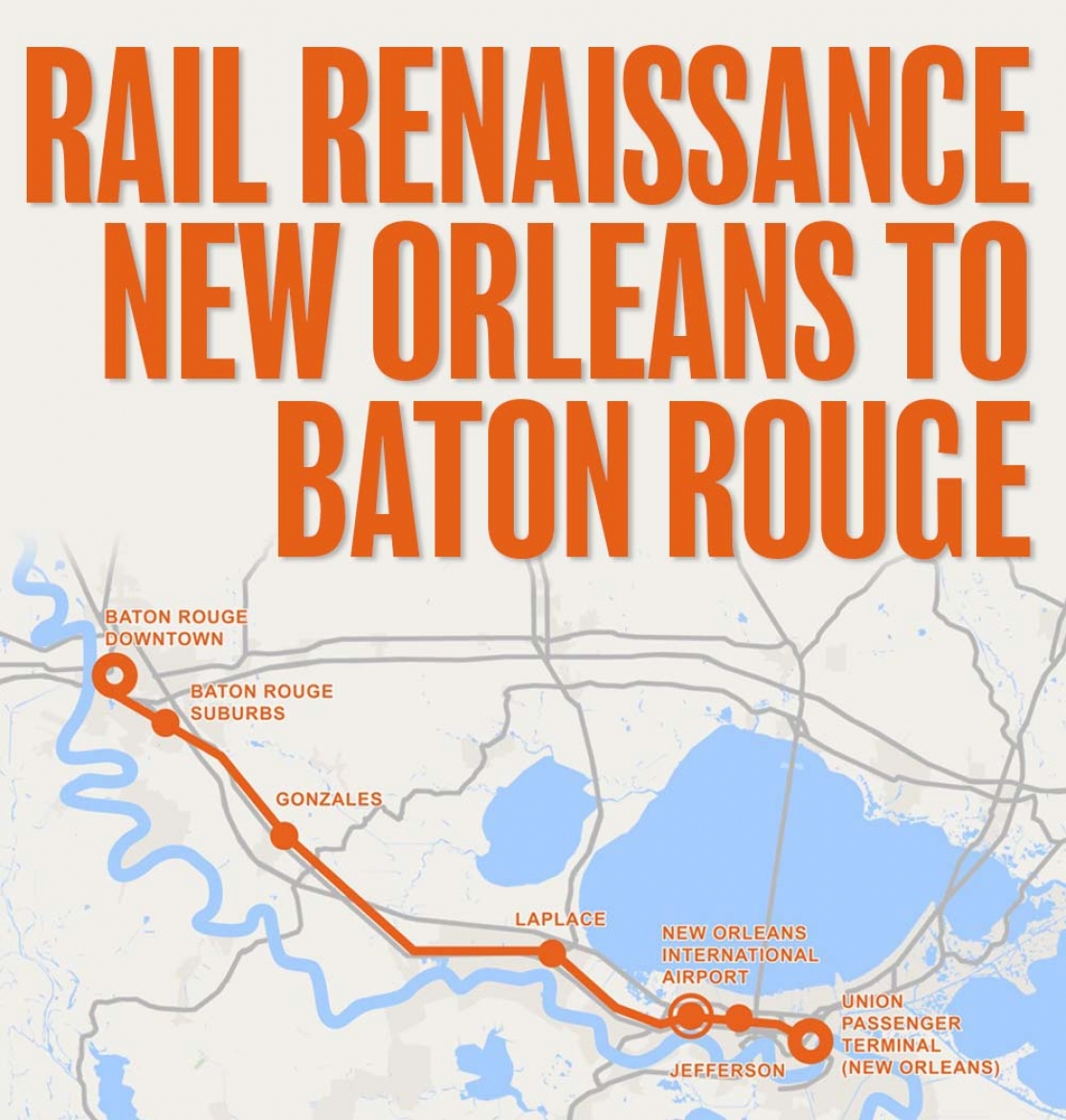

Baton Rouge to New Orleans passenger rail corridor

A robust passenger rail network is gaining attention once again at the national level as well. The Green New Deal currently being debated in Congress could potentially provide federal funding for intercity rail throughout the country. The federal Opportunity Zones program, which provides tax incentives for developments within designated census tracts, has set the stage in further incentivizing private investment. The planned rail stops in Baton Rouge and New Orleans at each end of the proposed intercity rail sit within these Opportunity Zones. The potential exists for public-private partnerships to come together and create transit-oriented developments at or near these stops, further cementing Baton Rouge’s Government Street and New Orleans’ Loyola Avenue as multi-modal corridors. New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and the communities between need to continue working together in this planning process knowing that funding streams can soon be made available from the public and/or private sector.

In an era when it’s easy to become distracted by new “smart city” technologies such as rideshare and autonomous vehicles, let us not forget that mass public transit remains the most efficient, sustainable, and equitable means of getting people places.

In an era when it’s easy to become distracted by new “smart city” technologies such as rideshare and autonomous vehicles, let us not forget that mass public transit remains the most efficient, sustainable, and equitable means of getting people places.