A New Opportunity For An Old Problem - Stop de Kindermoord

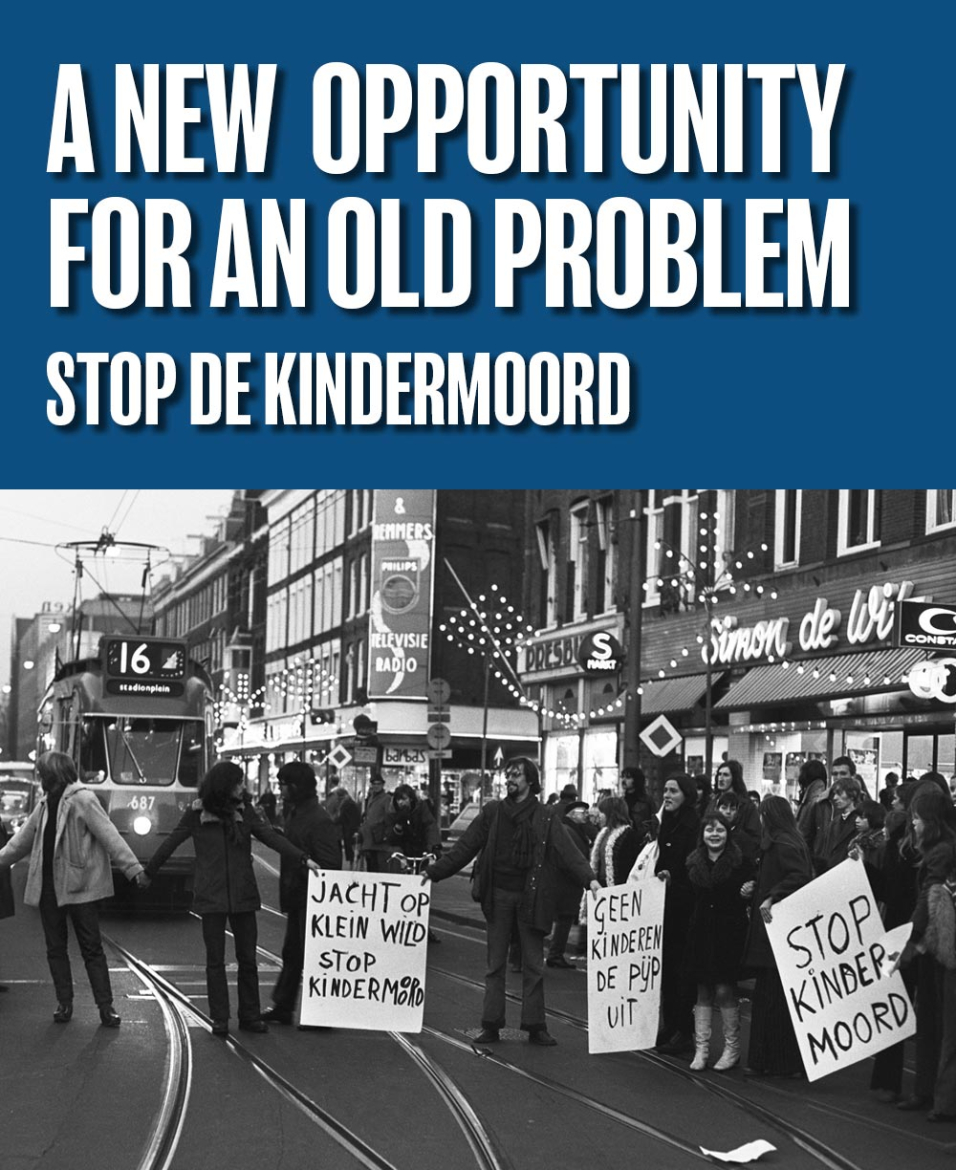

Action group Stop de Kindermoord occupied crossroads at Albert Cuypstraat in Amsterdam. Rob Mieremet / Anefo, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

While facing the economic and environmental impacts of the car is nothing new, there’s a way to frame the dilemma from a new perspective. In light of historical precedent and current infrastructure spending, an America less dependent on cars is possible.

Air pollution and the death and injury resulting from accidents are not the only downsides to our heavy dependency on the car. For decades, planners and architects have grappled with designing alternatives to reduce the highly valued land needed for parking in urban environments, the devastation to once vibrant neighborhoods torn apart by interstate highways, and the infrastructure required in urban and rural areas. Solutions are often approached from the question “How can we make the car better?” instead of “How can we replace the car?” America may seem too far gone, or too reliant on the motor vehicle to return to a less car-centric infrastructure; however, historical precedent tells us another way is possible.

The Netherlands is well known today as the biking capital of the world, but this wasn’t always the case. At the beginning of the 20th Century, bikes were the primary mode of transportation throughout the country. Then, through the 1960s, motor vehicles became increasingly common on Dutch streets as they became cheaper to produce, and the post-war economy boomed. The car was a technological revelation and how the world would be getting around for the foreseeable future, leading to heavy government spending on developing infrastructure centered on the motor vehicle. The car boom took a toll on the Netherlands, destroying entire neighborhoods to make way for superhighways. The growing number of traffic casualties peaked at 3,300 deaths in 1971. The Netherlands’ problems paralleled America’s as it transitioned to a car nation.

It was the high death toll resulting from auto accidents, specifically the 400 children that were killed that year, that sparked the movement known as Stop de Kindermoord, or “Stop the Child Murder.” People of all ages took to the streets to protest dangerous conditions for the nation’s children. Starting in Amsterdam and quickly taking over the country, the protests gained traction and got the attention of politicians and the public. By the 1980s, several Netherland cities had begun implementing bike-only routes, pushing more people to return to their bikes for commuting, pleasure, and the safety of their children. Today, over a quarter of all trips made in the Netherlands are made by bike, a percentage that grows daily.

Air pollution and the death and injury resulting from accidents are not the only downsides to our heavy dependency on the car. For decades, planners and architects have grappled with designing alternatives to reduce the highly valued land needed for parking in urban environments, the devastation to once vibrant neighborhoods torn apart by interstate highways, and the infrastructure required in urban and rural areas. Solutions are often approached from the question “How can we make the car better?” instead of “How can we replace the car?” America may seem too far gone, or too reliant on the motor vehicle to return to a less car-centric infrastructure; however, historical precedent tells us another way is possible.

The Netherlands is well known today as the biking capital of the world, but this wasn’t always the case. At the beginning of the 20th Century, bikes were the primary mode of transportation throughout the country. Then, through the 1960s, motor vehicles became increasingly common on Dutch streets as they became cheaper to produce, and the post-war economy boomed. The car was a technological revelation and how the world would be getting around for the foreseeable future, leading to heavy government spending on developing infrastructure centered on the motor vehicle. The car boom took a toll on the Netherlands, destroying entire neighborhoods to make way for superhighways. The growing number of traffic casualties peaked at 3,300 deaths in 1971. The Netherlands’ problems paralleled America’s as it transitioned to a car nation.

It was the high death toll resulting from auto accidents, specifically the 400 children that were killed that year, that sparked the movement known as Stop de Kindermoord, or “Stop the Child Murder.” People of all ages took to the streets to protest dangerous conditions for the nation’s children. Starting in Amsterdam and quickly taking over the country, the protests gained traction and got the attention of politicians and the public. By the 1980s, several Netherland cities had begun implementing bike-only routes, pushing more people to return to their bikes for commuting, pleasure, and the safety of their children. Today, over a quarter of all trips made in the Netherlands are made by bike, a percentage that grows daily.

Pressure group Stop de Kindermoord visits the House of Representatives, children with signs and banners at the KVP party. Bert Verhoeff for Anefo, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

As the number of cyclists grows, so do the issues dealing with infrastructure. Paths have become too small or worn, and expanded bike parking must be accommodated. Instead of letting this deter them, the Dutch have further committed to the bicycle. Most major cities have a dedicated team of civil servants who design, maintain, and improve the growing network of bike routes. The Dutch must maintain the infrastructure needed to support bicycles, yet it is minimal compared to the investment necessary for motor vehicle infrastructure.

The bikeshare program Blue Bikes are installed at Oretha Castle Haley and Martin Luther King Jr boulevards in New Orleans. Recent roadway improvements to a 14 block stretch of MLK Jr. Blvd. included the addition of bike lanes and high-visibility crosswalks. Katie Carter, Manning, APC.

The Netherlands presents a great case study showing it’s never too late for a society to change the course of its infrastructure purpose and design. We’ve already seen efforts in many cities across America. Cities such as Denver, Austin, and New Orleans have recently participated in The Final Mile Project, an experiment in which organizers work with politicians, local business owners, and community leaders to build over 335 miles of bike paths in five US cities over a two-year span, along with other improvements to biking and pedestrian infrastructure.

New Orleans has looked to the Netherlands for its innovations in water management for cities below sea level. Let’s look to them again for a path forward that reduces our dependency on cars. Through public pressure, government collaboration, and involvement, we can make our streets safer, cleaner, and more enjoyable.

New Orleans has looked to the Netherlands for its innovations in water management for cities below sea level. Let’s look to them again for a path forward that reduces our dependency on cars. Through public pressure, government collaboration, and involvement, we can make our streets safer, cleaner, and more enjoyable.

Fietsstraat or bike street is a road where bicycles share the path with cars. Usually bikes still dominate the road. John Tarantino, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.