Comparing Community Life in Two Cultures

Photo credit: Daniel chavez castro, by CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Growing up in a mixed family, I am part of two cultures. My Hispanic side comes from my mother, who was born in Honduras. When she was five, she migrated to Louisiana with her parents and six siblings. While I know it was rough for them in a new country with a new language, they survived and thrived through a heavy reliance on each other and the Hispanic community around them. That's a side of Hispanic culture that distinctly differs from how I was raised in a typical American neighborhood.

As Americans, we are taught to be individuals and private. Looking back at my upbringing in the American suburbs, I see how private we all were in hindsight. Although I was lucky enough to have a group of kids to play with, down the block or at the small park on my street, I didn't know much more about them than their names. I didn't know their families, and my family didn't know theirs. We were an open community of kids until we went home, where we lived quiet, separate lives. I wasn't aware of this phenomenon as a kid, but I remember visiting my grandparents, where being social with the surrounding community was a part of everyday life. When we traveled to Honduras, the language barrier didn't stop my brother and me from communicating the best we could with the neighborhood kids. And once the kids all went home, the community's social life didn't stop. Families would come together to eat or go to the beach.

As Americans, we are taught to be individuals and private. Looking back at my upbringing in the American suburbs, I see how private we all were in hindsight. Although I was lucky enough to have a group of kids to play with, down the block or at the small park on my street, I didn't know much more about them than their names. I didn't know their families, and my family didn't know theirs. We were an open community of kids until we went home, where we lived quiet, separate lives. I wasn't aware of this phenomenon as a kid, but I remember visiting my grandparents, where being social with the surrounding community was a part of everyday life. When we traveled to Honduras, the language barrier didn't stop my brother and me from communicating the best we could with the neighborhood kids. And once the kids all went home, the community's social life didn't stop. Families would come together to eat or go to the beach.

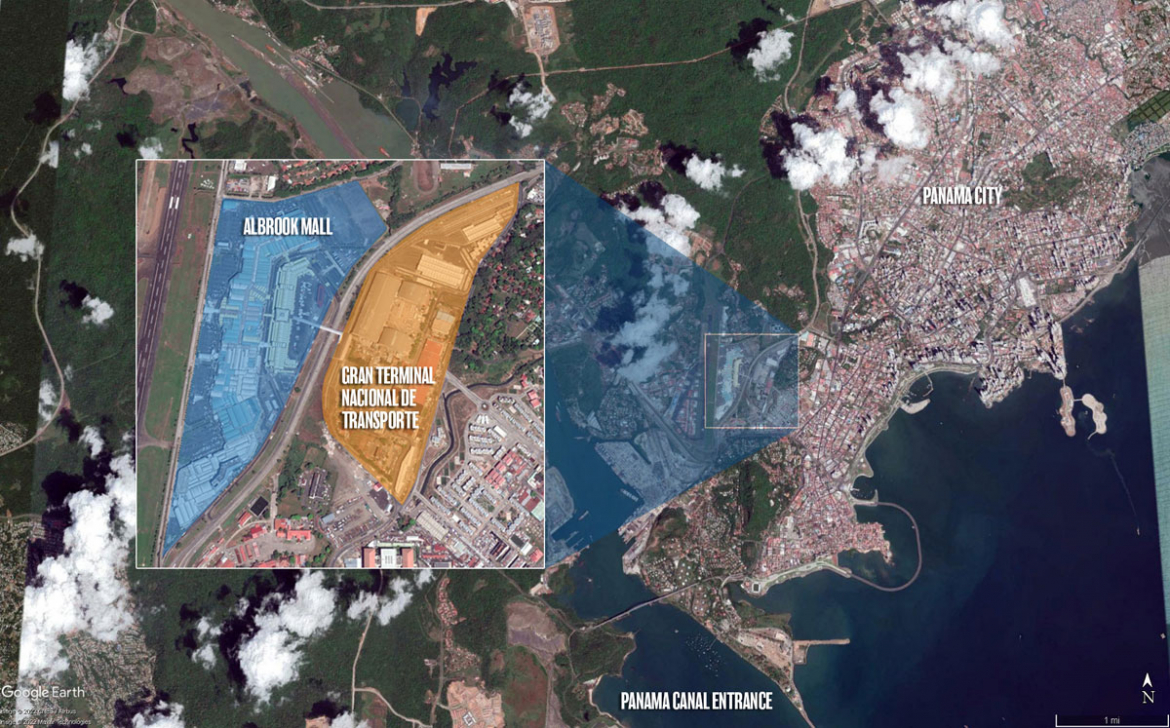

Later, when I was in architecture school, I took a closer look at the dual communities of my heritage through a project in Panama City. It dealt with the urbanization of the Canal Zone, once controlled by the U.S. Panama City's growth was limited because no one was allowed to build in the Canal Zone while it was under U.S. control. I focused on Panama's biggest mall, Albrook Mall, a defacto boundary between the urban city and the Canal Zone. In the United States, malls are dying. Shoppers have turned to online shopping, and driving in traffic to get to the mall is a hassle. Several malls have closed in the ten years I've lived in New Orleans. However, in Panama City, the mall is one of the best spots to go for an experience of community. Through my research, I found that Albrook Mall works so well because of its centralized location and the surrounding infrastructure. It is close to the city's urban core, across from a metro line terminal, and directly adjacent to Gran Terminal Nacional de Transporte, the hub for the bus line that serves the entire city. The easy access to the mall is what helped boost its popularity.

Photo credit: Chuck Holton, by CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, via Flickr Creative Commons

In the United States, this kind of easy access afforded by mass transit and urban density is limited to larger cities like New York and Chicago. An endless number of private cars drive us to our private homes. Most U.S. cities have limited public transportation, which requires citizens to invest in a car and spend hours in traffic. One study reports the average American spends eighteen days per year behind the wheel. Instead of the social benefits of walking in our cities, we are isolated in our cars. Tired at the end of the day, we don't want to drive farther to the mall, especially at peak traffic times.

During my studies, I read "The Remittance House," by Sarah Lynn Lopez, which highlighted the effects of migration on rural Mexico’s architecture. The article refers to a house built with money earned by a Mexican migrant in the United States who sends dollars (remits) to Mexico for the construction of his or her dream home. The goal of these migrants is to earn money and resources to send to their families back home. This was true with my mom's family in Honduras. My mother's family came from Honduras to start a new life, like most Hispanic immigrants from Central and South America. Eventually, my grandparents (with the help of my Aunts and Uncles) built their "Remittance House" back in Honduras, where we visited them. In their older years, they returned to the U.S. and my uncle's family moved in, continuing the family legacy.

Lopez notes that as migrants in the U.S. returned home to live in their "Remittance Houses," they brought back resources and American culture. They introduced American suburbs' privacy and relative isolation in their native environments. It is easy to forget that fences and doorbells in the American suburbs solidified the idea of a private home. Mexican migrants did not originally have doorbells or fences around their homes. The homes were open, and neighbors could visit at any point in the day. By bringing back door bells and fences, they created boundaries between themselves and their neighbors, eventually leading to isolation.

My Hispanic culture, with its sense of community, inspires me. As migrants have introduced American planning and design in their native homes, we can borrow design principles from these close-knit communities to strengthen our neighborhoods and cities. In America, the walkable city is not a new concept, but it will take time to realize that vision on a large scale since our city infrastructure is built around cars. I'd like to go back to when I was a kid and could walk down the street to a small park and interact with all the other kids. Only this time, I'd like our families to know each other from daily interaction on the street and in public spaces.

Citation:

Sarah Lynn Lopez, "The Remittance House" in the book "Buildings & Landscapes 17", No.2, Fall 2010.

During my studies, I read "The Remittance House," by Sarah Lynn Lopez, which highlighted the effects of migration on rural Mexico’s architecture. The article refers to a house built with money earned by a Mexican migrant in the United States who sends dollars (remits) to Mexico for the construction of his or her dream home. The goal of these migrants is to earn money and resources to send to their families back home. This was true with my mom's family in Honduras. My mother's family came from Honduras to start a new life, like most Hispanic immigrants from Central and South America. Eventually, my grandparents (with the help of my Aunts and Uncles) built their "Remittance House" back in Honduras, where we visited them. In their older years, they returned to the U.S. and my uncle's family moved in, continuing the family legacy.

Lopez notes that as migrants in the U.S. returned home to live in their "Remittance Houses," they brought back resources and American culture. They introduced American suburbs' privacy and relative isolation in their native environments. It is easy to forget that fences and doorbells in the American suburbs solidified the idea of a private home. Mexican migrants did not originally have doorbells or fences around their homes. The homes were open, and neighbors could visit at any point in the day. By bringing back door bells and fences, they created boundaries between themselves and their neighbors, eventually leading to isolation.

My Hispanic culture, with its sense of community, inspires me. As migrants have introduced American planning and design in their native homes, we can borrow design principles from these close-knit communities to strengthen our neighborhoods and cities. In America, the walkable city is not a new concept, but it will take time to realize that vision on a large scale since our city infrastructure is built around cars. I'd like to go back to when I was a kid and could walk down the street to a small park and interact with all the other kids. Only this time, I'd like our families to know each other from daily interaction on the street and in public spaces.

Citation:

Sarah Lynn Lopez, "The Remittance House" in the book "Buildings & Landscapes 17", No.2, Fall 2010.